As a developing leader in the digital education space, it’s vital to understand and articulate what guiding principles and values will shape my priorities and research in the present and also guide my work in the future. These same values should, of course, be reflected in my own digital footprint in as much as they inform my approach to leadership.

As a digital citizen advocate (ISTE Standard 7) and admissions official in higher education, I hope to elevate and address issues of access and equity, champion authenticity and integrity in digital spaces, and empower students, faculty, and staff to hold themselves accountable for their actions, roles and responsibilities in digital spaces.

Access:

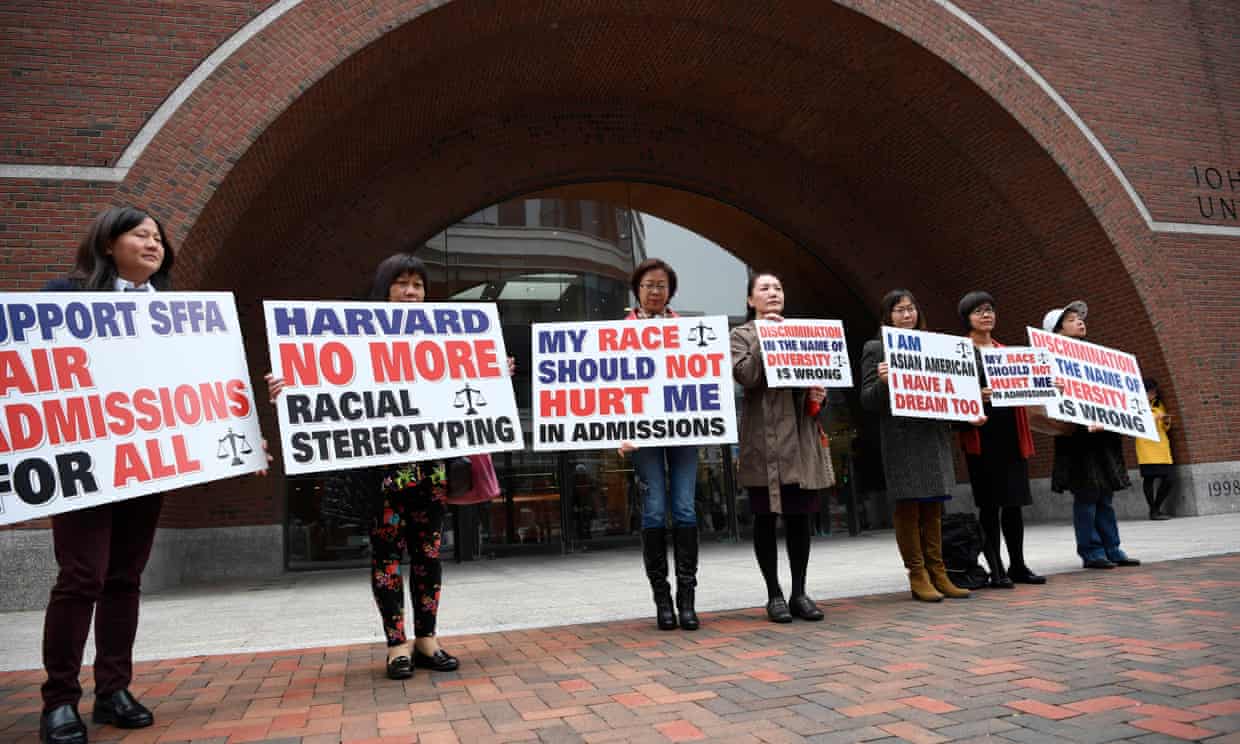

Issues pertaining to access and equity in the higher education admissions world have long persisted, but they’ve been especially well-documented in recent years as controversy after controversy has made headlines.

In 2019, a highly-publicized admissions scandal known as Operation Varsity Blues revealed conspiracies committed by more than 30 affluent parents, many in the entertainment industry, offering bribes to influence undergraduate admissions decisions at elite California universities. The scandal was not, however, limited to misguided actions of wealthy, overzealous parents; it included investigations into the coaches and higher education admissions officials who were complicit (Greenspan, 2019). This event—and others like it—highlight the fact that admissions decisions are not always objective and merit-based, and that those with the resources to game the system often do.

Unfortunately, there are many ways in which bias and inequity infiltrate the admissions process and undermine the accessibility of a high-quality college education. Standardized tests like the SAT or ACT for undergraduate admissions and the GRE or GMAT for graduate admissions come with their fair share of concerns. Research has oft-revealed how racial bias affects test design, assessment, and student performance, thus bringing biased data into the admissions process to begin with (Choi, 2020).

That said, admissions portfolios without standardized test scores have one less “objective” data point to consider in the admissions process, putting more weight on other more subjective pieces of an application (essays, recommendations, interviews, etc.). Most university admissions processes in the U.S.—both undergraduate and graduate—are human-centered and involve a “holistic review” of application materials (Alvero et al, 2020). A study by Alvero et al exploring bias in admissions essay reviews found that applicant demographic characteristics (namely gender and household income) were inferred by reviewers with a high level accuracy, opening the door for biased conclusions drawn from the essay within a holistic review system (Alvero et al., 2020).

It should go without saying that higher education institutions (HEIs) must seek to implement equitable, bias-free, admissions processes that guarantee access to all qualified students and prioritize diverse student bodies. Though technology may not—and likely should not, on its own—be able to offer a comprehensive solution to admissions bias, there are certainly some digital tools that, when utilized thoughtfully by higher education admissions professionals, can assist in the quest to prioritize equitable admissions practices, addressing challenges and improving higher education communities for students, faculty, and staff alike (ISTE standard 7a).

Without the wide recruiting net and public funding that large State institutions enjoy, the search for equitable recruiting/admissions practices and diverse classes may be hardest for small universities (Mintz, 2020). Taylor University—a small, private liberal arts university in Indiana—has turned to AI and algorithms for assistance in many aspects of the admissions and recruiting process. Platforms such as the Education Cloud by Salesforce “…use games, web tracking and machine learning systems to capture and process more and more student data, then convert qualitative inputs into quantitative outcomes” (Koenig, 2020).

Understandably, admissions officials want to admit students who have the highest likelihood of “succeeding” (i.e. persisting through to graduation). Noting that predictive tools must also account for bias that may exist in raw data reporting (like “name coding” or zip code bias), companies with products similar to the Education Cloud market fairer, more objective, more scientific ways to predict student success (Koenig, 2020). As a result, HEIs like Taylor are confidently using these kinds of tools in the admissions process to help counteract biases that grow situationally and often unexpectedly from how admissions officers review applicants, including an inconsistent number of reviewers, reviewer exhaustion, personality preferences, etc. (Pangburn, 2019).

Additionally, AI assists with more consistent and comprehensive “background” checks for student data reported on an application (e.g. confirming whether or not a student was really an athlete) (Pangburn, 2019). Findings from the Alvero et al. (2020) study suggest that AI use and data auditing might be useful in informing the review process by checking potential bias in human or computational readings (Alvero et al, 2020).

Regardless of its specific function in the process, AI and algorithms have the potential to make the admissions system more equitable by identifying authentic data points and helping schools reduce unseen human biases that can impact admissions decisions while simultaneously making bias pitfalls more explicit.

Without denying the ways in which technology has offered significant assistance to—and perhaps progress in—the world of higher education admissions, it’s still wise to think critically about the function of AI and algorithms in order to ensure they’re helping more than they’re hurting. There is a persistent and reasonable concern among digital ethicists that AI and algorithms simply mask and extend preexisting prejudice (Koenig, 2020). It is dangerous to assume that technology is inherently objective or neutral, since technology is still created or designed by a human with implicit (or explicit) bias. As author Ruha Benjamin states in Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (2019), “…coded inequity makes it easier and faster to produce racist outcomes.” (p. 12) Thus, there is always a balance to be struck where technology is concerned.

As an admissions official at a small, private, liberal arts institution, I am well aware of the challenges presented to HEI recruitment and admissions processes in the present and future, and am heartened to consider the possibilities that AI and algorithms might bring to the table, especially regarding equitable admissions practices and recruiting more diverse student bodies. However, echoing the sentiments of The New Jim Code, I do not believe that technology is inherently neutral, and I do not believe that the use of AI or algorithms are comprehensive solutions for admissions bias. Higher education officials must proceed carefully, thoughtfully, and with the appropriate amount of skepticism in order to allow tech tools to reach their fullest potential in helping address issues of access, equity, and bias in higher education admissions (ISTE standard 7a).

Authenticity:

Anyone with a digital footprint has participated in creating—knowingly or unknowingly—a digital identity for themselves. Virtual space offers people the freedom “…to choose who they want to be, how they want to be, and whom they want to impress, without being constrained by the norms and behaviors that are desirable in the society to which they belong” (Camacho et al., 2012, p. 3177). The internet provides new opportunities for spaces for learning, working, and socializing, and all of these spaces offer opportunities for identity to be renegotiated (Camacho, 2012). It is a worthy—if not simple—endeavor to pursue authenticity and integrity within any kind of digital identity, digital media representation, or online interaction.

Interactive communication technologies (ICTs) complicate meaningful pursuits of authenticity. These digitally-mediated realms of human interaction challenge what we see as authentic and make it harder to tell the difference between what is “real” and what is “fake” (Molleda, 2010). One need look no further than “reality” TV, social media personas, and journalistic integrity in the era of “fake news” to understand that not all claims of authenticity in media are substantive.

This does not mean, however, that authenticity in digital space fails to have inherent value or is impossible to achieve. An ethic of authenticity goes beyond any kind of plan, presentation, or strategic marketing campaign; authenticity is about presenting the essence of what already exists and whether (or not) it has the ability to live up to its own and others’ expectations and needs (Molleda, 2010). Exercising authenticity includes making informed decisions about protecting personal data while still curating the digital profile one intends to reflect (ISTE Standard 7d). Exercising authenticity also contributes to a wise use of digital platforms and healthy, meaningful online interactions (ISTE standard 7b).

In a comprehensive literature review, Molleda (2010) found that several pervasive themes, definitions, and perceptions of authenticity consistently surfaced across a variety of disciplines. Taken as a whole, Molleda (2010) asserts that these claims may be used to “index” or measure authenticity to the extent that they are present in any given communication or media representation. Some of these key aspects of authenticity include:

- Being “true to self” and stated core values

- Maintaining the essence of the original (form, idea, design, product, service, etc.)

- Living up to others’ expectations and needs (e.g. delivering on promises)

- Being original and thoughtfully created vs. mass produced

- Existing beyond profit-making or corporate/organizational gains

- Deriving from true human experience

Molleda (2010) concludes that consistency between “the genuine nature of organizational offerings and their communication is crucial to overcome the eroding confidence in major social institutions” (p. 233). I for one hope to continue embodying an ethic of authenticity in both my personal and professional work—in digital spaces and otherwise—in order to set the stage for that consistency and to bolster societal confidence in the institution I’m a part of.

Accountability

The digital realm is an extended space where human interactions take place, and the volume of interactions taking place in digital spaces is only increasing. As with any segment of human society, human flourishing, creativity, and innovation takes place in spaces where people feel safe and invested in the community in which they find themselves. Thus, as a digital leader, it is important to empower others to seriously consider their individual roles and responsibilities in the digital world, inspiring them to use technology for civic engagement and improving their communities, virtually or otherwise (ISTE standard 7a).

Humans do not come ready-made with all of the savvy needed to engage with media and online communications in wise ways. Media literacy education is needed to provide the cognitive and social scaffolding that leads to substantive, responsible civic engagement (Martens & Hobbs, 2015). Media literacy is also a subset of one’s own ethical literacy, which is the ability to articulate and reflect upon one’s own moral life in order to encourage ethical, reasoned actions. As a digital citizen advocate and marketing professional, I hope to support educators in all kinds of contexts—both personal and professional—to examine the sources of online media, be mindful consumers of online content, and consistently identify underlying assumptions in the content we interact with (ISTE standard 7c). In an effort to be digitally wise and to “beat the algorithm” in digital spaces (both literally and metaphorically speaking), we must self-identify potential echo chambers and intentionally seek out alternative perspectives. This requires a commitment to media literacy education in all kinds of formal and informal environments.

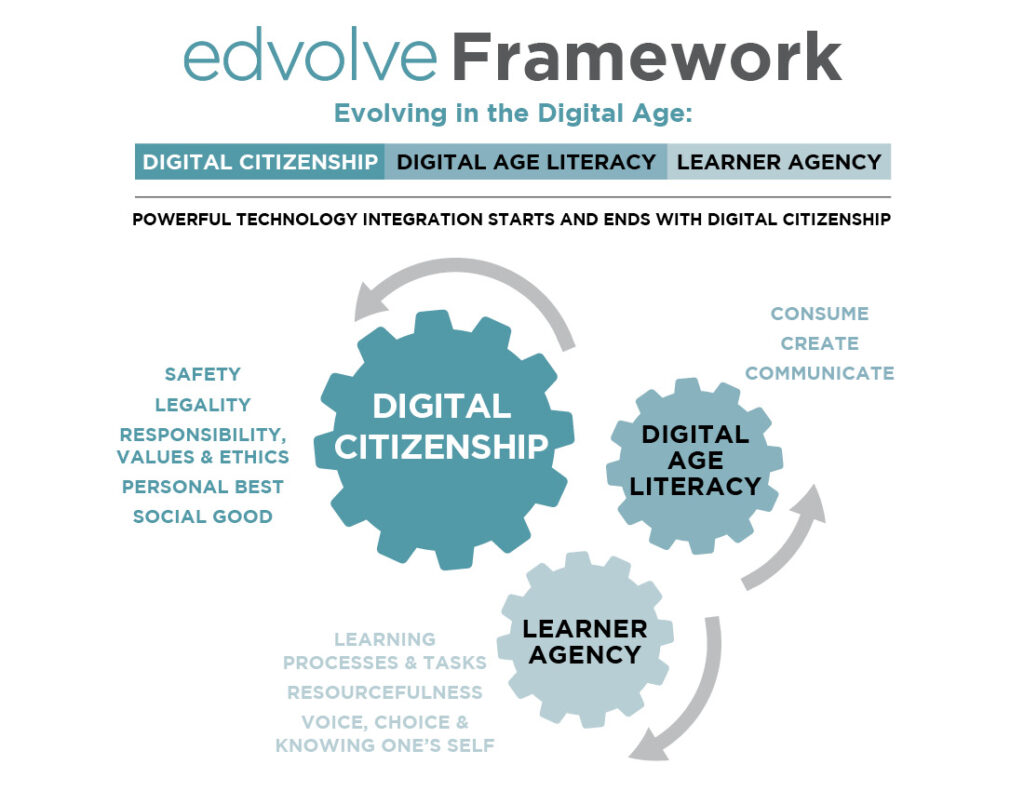

Media literacy education equips educational leaders and students to foster a culture of respectful, responsible online interactions and a healthy, life-giving use of technology (ISTE standard 7b). According to Hobbs (2010), media literacy is a subset of digital literacy skills involving:

- the ability to access information by locating and sharing materials and comprehending information and ideas

- the ability to create content in a variety of forms, making use of digital tools and technologies;

- the ability to reflect on one’s own conduct and communication by applying social responsibility and ethical principles; (ISTE standard 7b)

- the ability to take social action by working individually and collaboratively to share knowledge and solve problems as a member of a community; (ISTE standard 7a)

- the ability to analyze messages in a variety of forms by identifying the author, purpose, and point of view and evaluating the quality and credibility of the content. (ISTE standard 7c)

In a study conducted with 400 American high school students, findings showed that students who participated in a media literacy program had substantially higher levels of media knowledge and news/advertising analysis skills than other students (Martens & Hobbs, 2015). Perhaps more importantly, information-seeking motives, media knowledge, and news analysis skills independently contributed to adolescents’ proclivity towards civic engagement (Martens & Hobbs, 2015), and civic engagement naturally requires dialogue with others within and outside of an individual’s immediate circle. In other words, the more students were able to critically consider the content they were consuming and the motives behind why they were consuming it, the more they wanted to engage with alternative perspectives and be active, responsible, productive members of a larger community (ISTE standard 7a).

This particular guiding principal is large in scope; it’s importance and relevance isn’t limited to a specific aspect of my professional context as much as it helps define an ethos for all actions, communication, and consumption that takes place in the digital world. In order to hold ourselves accountable for our identities and actions online we must exercise agency. The passive internet user/consumer is the one most likely to get caught in an echo chamber, develop destructive online habits, and communicate poorly in virtual space. The digitally wise will make consistent efforts to challenge their own thinking, create safe spaces for communication, intentionally seek out alternative voices, and actively reflect on their contributions to an online community, ultimately making digital spaces a little bit better than when they found them.

References:

Alvero, A.J., Arthurs, N., Antonio, A., Domingue, B., Gebre-Medhin, B., Gieble, S., & Stevens, M. (2020). AI and holistic review: Informing human reading in college admissions from the proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 200–206. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3375627.3375871.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity.

Camacho, M., Minelli, J., & Grosseck, G., (2012). Self and identity: Raising undergraduate students’ awareness on their digital footprints. Procedia Social & Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3176-3181.

Choi, Y.W. (2020, March 31). How to address racial bias in standardized testing. Next Gen Learning. https://www.nextgenlearning.org/articles/racial-bias-standardized-testing

Greenspan, R. (2019, May 15). Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman’s college admissions scandal remains ongoing. Here are the latest developments. Time. https://time.com/5549921/college-admissions-bribery-scandal/

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. The Aspen Institute Communications and Society Program & the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. https://knightfoundation.org/reports/digital-and-media-literacy-plan-action/

Koenig, R. (2020, July 10). As colleges move away from the SAT, will algorithms step in? EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-07-10-as-colleges-move-away-from-the-sat-will-admissions-algorithms-step-in

Martens, H. & Hobbs, R. (2015). How media literacy supports civic engagement in a digital age. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23, 120–137.

Mintz, S. (2020, July 13). Equity in college admissions. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/equity-college-admissions-0

Molleda, J. (2010). Authenticity and the construct’s dimensions in public relations and communication research. Journal of Communication Management,14(3), 223-236. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.spu.edu/10.1108/13632541011064508

Pangburn, D. (2019, May 17). Schools are using software to help pick who gets in. What could go wrong? Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90342596/schools-are-quietly-turning-to-ai-to-help-pick-who-gets-in-what-could-go-wrong