Research in higher education looks very different today than it did even ten years ago. Academics who, not so very long ago, were well acquainted with physical library study spaces and large collections of peer-reviewed academic journals, find themselves in a digitized world of research with unprecedented access to information and virtual repositories of human meaning-making activity. The nature and culture of research in higher education is shifting, including that which is considered “worthy” content to explore when conducting research in all kinds of disciplines. One need look no further than the APA reference guide and the ever-expanding list of possible resources (e.g.. YouTube videos and TED talks, podcasts, blog posts, etc.) to note that the “rules” of research are expanding, and must expand, alongside our access to information.

As a current doctoral student (and someone who received my initial graduate degree a decade ago), I am curious about the ways the research sector of higher education has changed over time. How are undergraduate students being taught to conduct research? What kind of shifts have been made due to new tools and technology platforms that assist in the research process? What cultural shifts are happening in graduate and doctoral programs, and are these cultural shifts impacting research strategy?

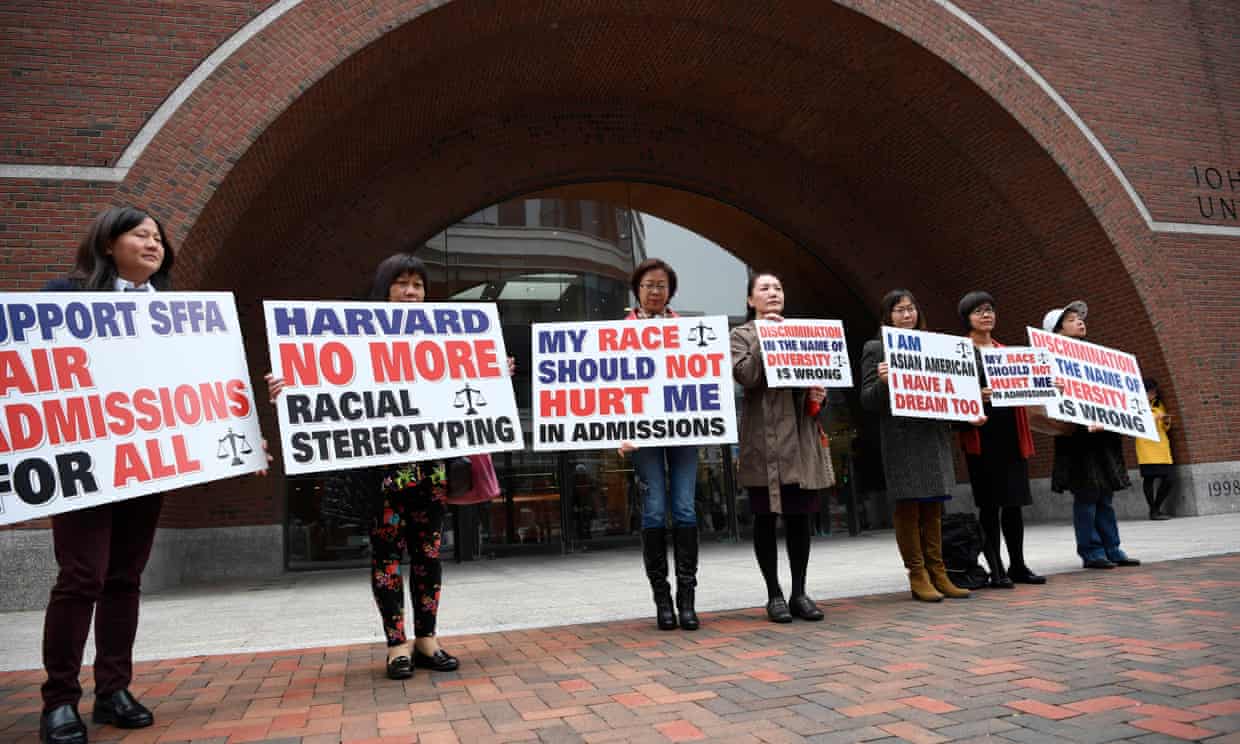

Jonbloed et al. (2008) posit that higher education has an expanding set of stakeholders and thus a continually shifting societal expectation of what a university’s public obligation is. Early universities provided education exclusively for clergy and societal elites, but over the centuries, higher education has been democratized such that there are many invested parties and participants with competing paradigms and priorities. Indeed, one of the major, ongoing, accelerated shifts in higher education is the diversification of students, staff, and faculty and the role that universities can/should play as advocates of–and vehicles for–social justice (Brennan & Teichler, 2008). We also now live in a “knowledge society” where knowledge is considered the solution to everything and the key to personal and societal advancement (Jonbloed et al., 2008). Thus, higher education institutions (HEIs) are driven to make teaching and research more publicly accountable, often restructuring programs and creating new ones to meet modern societal demands and forfeiting, or “reorienting,” long standing academic norms and values along the way (Jonbloed et al., 2008).

Even the doctorate degree, a terminal, research-based degree program which is typically the highest academic degree that can be awarded by a university, isn’t immune to change. There is an increasing demand for doctoral programs to become more relevant, to produce academics with transferable skills in their field in addition to research skills, and to even be more sensitive to issues of employability that extend beyond creating new academics who scarcely step outside the “ivory tower” of a university campus (Park, 2005). This requires attention to the course structure and modality of a doctoral program, the quality of the mentorship provided, the diversity of students within the program, and an expansion of that which is considered sufficient, valuable evidence of research contributions in a given field.

At the undergraduate level, much focus is given to the development of research skills as a form of information or digital literacy. K-12 schools and districts across the United States differ greatly in their approach to teaching digital literacy skills. Thus, undergraduate students at HEIs come into lower division classes with a wide range of background and abilities (or lack thereof) informing their approach to research. In a case study conducted at Texas Christian University (TCU) by Huddleston et al. (2019), faculty were surveyed to determine what research skills they felt were most needed and valuable for undergraduate students to have, and which skills undergraduate students tended to struggle with most. A list of nine core skills for research success was produced based on faculty responses:

- Topic selection

- Search strategy

- Finding resources

- Differentiating source types

- Evaluating sources

- Synthesizing information

- Summarizing information

- Citing sources

- Reading and understanding citations

Perhaps unsurprisingly, faculty overwhelmingly felt that the skill they most wanted students to master by the time they graduated was the ability to critically evaluate information and sources. This was, however, also found to be the weakest skill that undergraduate TCU students possessed, and that they were least likely to be able to do at a satisfactory level upon graduation (Huddleston et al., 2019). It is no coincidence that the ability to think critically about an information source is needed now more than ever due to the overwhelming amount of information and sources available on the world wide web. While access to valuable, credible sources of information expands, students need to be able to recognize “worthy” material in dynamic ways which allow them to differentiate their source types appropriately. Certainly not all valuable research material is limited to the contents of academic journals, but neither is every blog post worthy of scholarly consideration. In this case study, Huddleston et al. (2019) note that the university library/librarians are important resources and guides when it comes to information literacy instruction, and a number of suggestions were made to help increase the visibility of librarians at the department level, leveraging their knowledge and training alongside faculty in a collaborative approach to teaching undergraduates needed research skills.

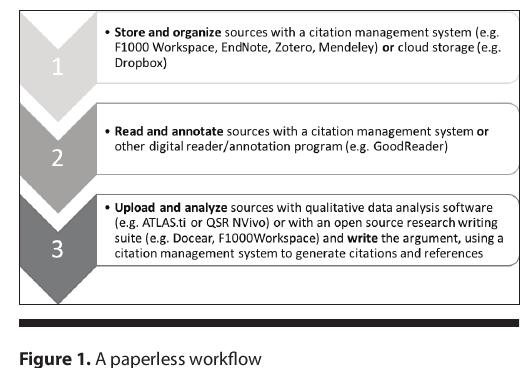

There is no denying that a certain level of digital and informational literacy is essential in all areas of higher education given that “research outputs across the academic disciplines are almost exclusively published electronically,” and therefore “organizing and managing these digital resources for purposes of review…are now essential skills for graduate study and life in academia.” (Lubke et al., 2017, p. 285) Of course, in the year 2021, there are also a myriad of digital tools available that not only assist in the research process, but make it easier to practice information literacy and grow a researcher’s individual technical savvy. Assuming the literature review (i.e. research paper) is the most frequent research-based activity conducted in higher education, especially at the graduate level, Lubke et al. (2017) propose a simple, 3-step framework which can become the essential workflow for a paperless research project.

As the image suggests, stage one begins with selecting a digital tool to store and analyze sources. Some suggested platforms include Zotero, EndNote, F1000 Workspace, RefWorks, and Mendeley. Each tool has its own strengths and weaknesses, but generally speaking, each is an example of a digital tool that assists researchers in methodically storing and organizing possible source material for consideration, both in the current research process and for possible future use (e.g. dissertation). Once sources have been selected and stored, researchers may then move to stage two where they may read, annotate, and analyze their sources. This is where weak sources may be removed from consideration and where important pieces of information are mined and commented on in preparation for creating an academic argument (Lubke at al., 2017). In the annotation phase, digital tools like GoodReader can be used to take notes and highlight a text; then, annotated versions of sources may be saved separately from the original. Finally, in stage three, researchers may choose to employ Qualitative data analysis software (QDAS) like QSR NVivo to synthesize themes and pull together information from across sources, ultimately drawing conclusions for publication.

The nature of research in higher education–and really, higher education itself–has changed drastically over the course of the last couple of decades. Higher education is expanding in its scope and purpose, and there is increasing demand for academic research to have immediate, practical value. When conducting research, the most frequent problem faced by students and academics at all levels is what to do with the vast amounts of information we now have access to: how to source it, organize it, and analyze it critically. Direct instruction in digital and information literacy continues to be a need in postsecondary education (both undergraduate and graduate), but there are a number of tools available that can be powerful aids in the research process, expanding our knowledge base and extending our capacity to think critically about sources, thus also expanding our potential for innovation. There is no doubt that the nature of research will continue to evolve alongside the digital world…are we ready to consider the possibilities?

References

Brennan, J. & Teichler, U. (2008). The future of higher education and of higher education research. Higher Education, 56(3), p. 259-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2003.9967102

Huddleston, B., Bond, J., Chenoweth, L., & Hull, T. (2019). Faculty perspectives on undergraduate research skills: Nine core skills for research success. Reference & User Services Quarterly (59)2, pp. 118-130.

Jonbloed, B., Enders, J., & Salerno, C. (2008). Higher education and its communities: Interconnections, interdependencies and a research agenda. Higher Education, 56(3), p.303-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2003.9967102

Lubke, J., Britt, V., Paulus, T., & Atkins, D. (2017). Hacking the literature review: Opportunities and innovations to improve the research process. Reference and User Services Quarterly (56)4, p. 285-295.

Park, C. (2005). New variant PhD: The changing nature of the doctorate in the UK. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 27(2), p.189–207. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1360080050012006