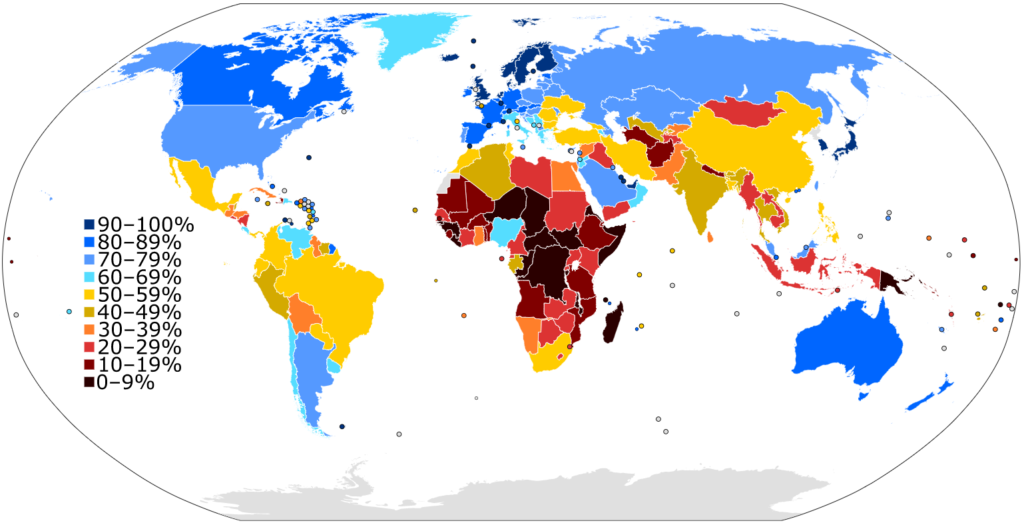

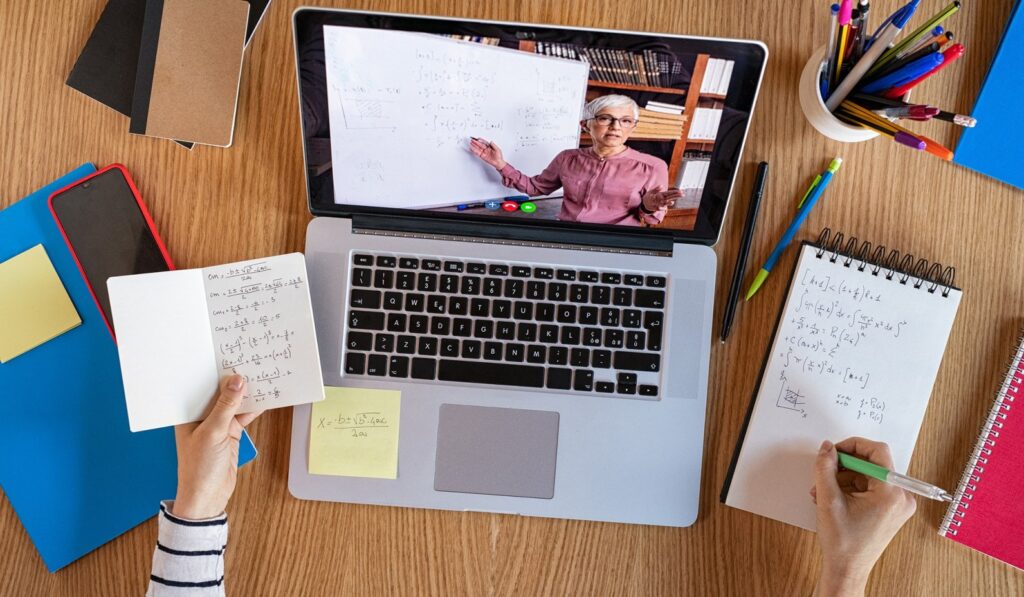

Though the digital age may not actually be changing a student’s capacity to learn, it’s certainly changing how students access content and participate in learning environments. Digital technology thoroughly transforms the way in which we create, manage, transfer, and apply knowledge (Duderstadt, Atkins, & Van Houweling, 2002). Unsurprisingly, it’s also changing how educators teach, particularly with technology-mediated instruction in higher education. The demand for online instruction is on the rise. In the United States alone, the number of higher education students enrolled in online courses increased by 21% between fall 2008 and fall 2009, and the rate of increase has only grown in recent years, both nationally and globally (Bolliger & Inan, 2012). Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 has also necessitated a radical—though in some cases temporary—shift to online learning modalities at all educational levels across the globe.

Fortunately, there’s evidence to support that digital education incorporation can enhance pedagogy and improve overall student performance at the college level. An extensive, multi-year case study conducted at the University of Central Florida showed that student success in blended programs (success being defined as achieving a C- grade or higher) actually exceeded the success rates of students in either fully online or fully face-to-face programs (Dziuban, C., Hartman, J., Moskal, P., Sorg, S., & Truman, B., 2004).

In the switch to online teaching and learning, a clear challenge is presented: teaching faculty are faced with a need to move their programs and classes into online/flexible learning formats, regardless of their discipline or their expertise/ability to do so. It is not uncommon for teachers, no matter the level at which they teach, to be asked to implement something new in their classroom without sufficient support, professional development, or resources to make the implementation successful. The need for appropriate training becomes that much more pressing when educators are asked to engage with an entirely different instruction medium from that which they are accustomed to. In the case of blended or online learning, many faculty will need to develop completely new technological and/or pedagogical skills. While a number of scholars have conducted investigations into the effectiveness of blended or online learning, very few have provided guidance for adoption at the institutional level (Porter, Graham, Spring, & Welch, 2014).

Far from being a comprehensive guide, this post seeks to explore a few major themes and best practices for online learning in postsecondary education which may prove helpful for teaching professionals and higher education institutions heading into an otherwise unfamiliar world of digital education.

Create a Learning Community:

Digital education is made possible by computers and the internet. In the age of the Internet, the computer is ultimately used most to provide connection, whether that be through social media, e-commerce, gaming, publications, or education (Weigel, 2002). Technology-mediated education is making it possible for students to participate in programs, access content, and connect in ways they were previously unable to. Rather than viewing the Internet as a necessary evil for distance learning that ultimately begets isolated student learning experiences, digital education should, first and foremost, be connective and communal. This means a professor accustomed to lecture-based learning in a physical classroom may need to consider a new approach in order to make space for student voice in the learning process. In an online context, this means there should be dynamic opportunities for students to engage in debate, reflection, collaboration, and peer review (Weigel, 2002).

Beyond Information Transfer:

Learning and schooling no longer have the same direct relationship they had for most of the 20th century; devices and digital libraries allow anyone to have access to information at any time (Wilen, 2009). Schools, teachers, and even books no longer hold the “keys to the kingdom” as sources of information. Higher education, then, will not function effectively as a large-scale effort to teach students information through a standardized curriculum. Rather, education must be a highly relevant venture that enables individual students to do something with the virtually endless information and resources they have access to (Wilen, 2009).

Relevance:

If university instructors are going to seriously account for the rich background experiences, varied motivations, and personal agency of their postsecondary students, they must also take into account the larger “lifewide” learning that takes place within the life of most college students (Peters & Romero, 2019). Student learning at any age is both formal and informal, and what takes place in a formal classroom environment is influenced by informal learning and daily living that takes place outside of it. Likewise, if deep learning takes place, a student’s world and daily life should be altered by the creation of new schemas and the learning that has taken place in a formal classroom environment.

In a multicase and multisite study conducted by Mitchell Peters and Marc Romero in 2019, 13 different fully-online graduate programs in Spain, the US, and the UK were examined in order to analyze learning processes across a continuum of contexts (i.e., to understand to what extent learning was used by the student outside of the formal classroom environment). Certain common pedagogical strategies arose across programs in support of successful student learning and engagement including: developing core skills in information literacy and knowledge management, community-building through discussion and debate forums, making connections between academic study and professional practice, connecting micro-scale tasks (like weekly posts) with macro-scale tasks (like a final project), and applying professional interests and experiences into course assignments and interest-driven research (Peters & Romero, 2019). In many regards, each of these pedagogical strategies is ultimately teaching students to “learn how to learn” so that the skills they cultivate in the classroom can be applied over and over again elsewhere.

Professional Development:

Still there remains the question of implementation. In order for the mature adoption of digital education to take place, faculty need to be given time and training to help them develop new technological and pedagogical skills. If an institution fails to provide sufficient opportunities for professional development, many faculty members will likely fail to fully embrace the shift to an online format, and will instead replicate their conventional teaching methods in a manner that isn’t compatible with effective online instruction (Porter, et al., 2014). If higher education institutions are committed to delivering high quality instruction in all contexts, it will be important for administrators to retain qualified instructors who are motivated to teach online and who are satisfied with teaching online (Bolliger, Inan, & Wasilik, 2014).

In a 2012-2013 survey of 11 higher education institutions reporting on their implementation of blended learning programs, Wendy Porter et al found that every university surveyed provided at least some measure of professional development to support faculty in the transition. Each university had their own customized approach, but the fact that developmental support was prioritized in some regard remained consistent across all of the institutions in the survey. Strategies used for professional development in digital learning included presentations, seminars, webinars, live workshops, orientations, boot camps, instructor certification programs for online teaching, course redesign classes, and self-paced training programs (Porter et al., 2014).

Digital Literacy:

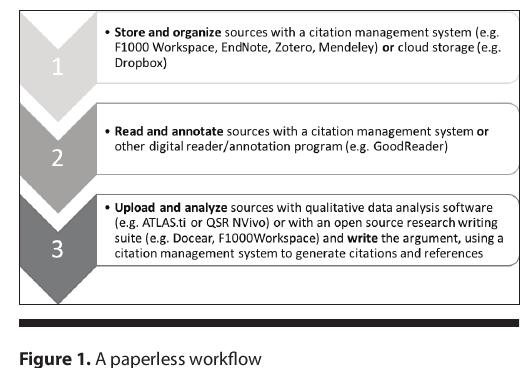

Digital literacy among higher education faculty can’t be taken for granted. A recent Action Research study aimed at exploring the digital capacity and capability of higher education practitioners found that, though the self-reported digital capability of an individual may be relatively high, it did not necessarily relate to the quality of their technical skills in relation to their jobs (Podorova et al., 2019). Survey results from the study also showed that the majority of practitioners (41 higher education professors in Australia) were self-taught in the skills they did possess, receiving very little formal training or support from their employer, even with technology devices and tools directly pertaining to teaching and assessment (Podorova et al., 2019). Though this data relates to a specific case study, it is not difficult to imagine that higher education faculty in institutions all over the world might report similar experiences. If faculty aren’t given sufficient technological support and training, they will be less satisfied in their work and, ultimately, the student experience will suffer (Bolliger, et al., 2014).

Institutional Adoption:

In addition to providing sufficient technological or pedagogical resources, it is important for university administrators to communicate the purpose for online course adaptation. In a later study conducted by Wendy Porter and Charles Graham in 2016, research indicated that higher education faculty more readily pursued effective adoption strategies when they were in alignment with the institution’s administrators and the stated purpose for doing so (Porter & Graham, 2016). If faculty members are, in essence, adult learners being asked to acquire new skills, it is essential to take their own motivations for learning into account. Additionally, sharing data and course feedback internally from early-adopters to online instruction can go a long way in helping reticent faculty feel ready to approach online learning (Porter & Graham, 2016). Institutional support is cited frequently in literature pertaining to faculty satisfaction in higher education. In the domain of online learning, institutional support looks like: providing adequate release time to prepare for online courses, fair compensation, and giving faculty sufficient tools, training, and reliable technical support (Bolliger et al., 2014).

One effective approach to professional development for online learning places professors in the seat of the student. At Hawaii’s Kapi’olani Community College on the island of Oahu, Instructional Designer Helen Torigoe was charged with training faculty in the process of converting courses for online delivery. In response, Torigoe created the Teaching Online Prep Program (TOPP) (Schauffhauser, 2019). In TOPP, faculty participate in an online course model as a student, using their own first-hand experience to inform their course creation. As they participate in the course, faculty are able to use the technology that they will be in charge of as an instructor (programs like Zoom, Padlet, Flipgrid, Adobe Spark, Loom, and Screencast-O-Matic), gaining comfort and ease with the tools and increasing their overall digital literacy. Faculty also get a comprehensive sense for the student experience while concurrently creating an actual course template and receiving guidance and support from the TOPP course coordinator. Such training is mandatory for anybody teaching online for the first time at Kapi’olani Community College. A “Recharge” workshop has also been created to help faculty engage in continued learning for best practice in digital education, ensuring that faculty do not become static in their teaching methods and are consistently exposed to new tools and strategies for digital education (Schauffhauser, 2019). Institutions that participate in online education need to provide adequate training in both pedagogical issues and technology-related skills for their faculty, not only when developing and teaching online courses for the first time, but as an ongoing priority in faculty professional development (Bolliger et al., 2014).

Summary:

The number of graduate courses and programs that must be offered in an online format is increasing in many higher education environments. Effective online educators will acknowledge the unique needs of their postsecondary learners: that their students need to have their background experiences and context utilized in the learning process, that their learning needs to be relevant to their life and work, and that their learning needs to be providing them with actionable skills and learning strategies that ultimately change how they interact with their world. Effective online learning will also provide ample space for student connection and active participation. This means there should be dynamic opportunities for students to engage in debate, reflection, collaboration, and peer review (Weigel, 2002). Additionally, online learning ought to be a highly relevant venture that enables individual students to do something with the virtually endless information and resources they have access to (Wilen, 2009). Yet in order for the mature adoption of digital education to take place, faculty need to be given time and training to help them develop new technological and pedagogical skills. This training needs to happen with initial adoption and as an ongoing venture. One example of highly effective faculty professional development can be found in Instructional Designer Helen Torigoe’s Teaching Online Prep Program (TOPP) (Schaffhauser, 2019). In this program the instructors become the students as they familiarize themselves with a new learning system, create a customized course template, and get feedback and support from knowledgeable online educators. In short, well-equipped, well-trained, and well-supported graduate faculty are fertile ground for effective online education.

References

Bolliger, D. U., Inan, F. A., & Wasilik, O. (2014). Development and validation of the online instructor satisfaction measure (OISM). Educational Technology Society, 17(2), 183–195.

Duderstadt, J., Atkins, D., Van Houweling, D. (2002). Higher education in the digital age: Technology issues and strategies for American colleges and universities. Praeger Publishers.

Dziuban, C., Hartman, J., Moskal, P., Sorg, S., & Truman, B. (2004). Three ALN modalities: An institutional perspective. In J. R. Bourne, & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Elements of quality online education: Into the mainstream (127–148). Sloan Consortium.

Peters, M. & Romero, M. (2019) Lifelong learning ecologies in online higher education: Students’ engagement in the continuum between formal and informal learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(4), 1729.

Podorova, A., Irvine, S., Kilmister, M., Hewison, R., Janssen, A., Speziali, A., …McAlinden, M. (2019). An important, but neglected aspect of learning assistance in higher education: Exploring the digital learning capacity of academic language and learning practitioners. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(4), 1-21.

Porter, W., & Graham, C. (2016). Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(4), 748-762.

Porter, W., Graham, C., Spring, K., & Welch, K. (2014). Blended learning in higher education: Institutional adoption and implementation. Computers & Education, 75, 185-195.

Schaffhauser, D. (2019). Improving online teaching through training and support. Campus Technology. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2019/10/30/improving-online-teaching-through-training-and-support.aspx

Weigel, V.B. (2002) Deep learning for a digital age. Jossey-Bass.

Wilen, T. (2009). .Edu: Technology and learning environments in higher education. Peter Lang Publishing.