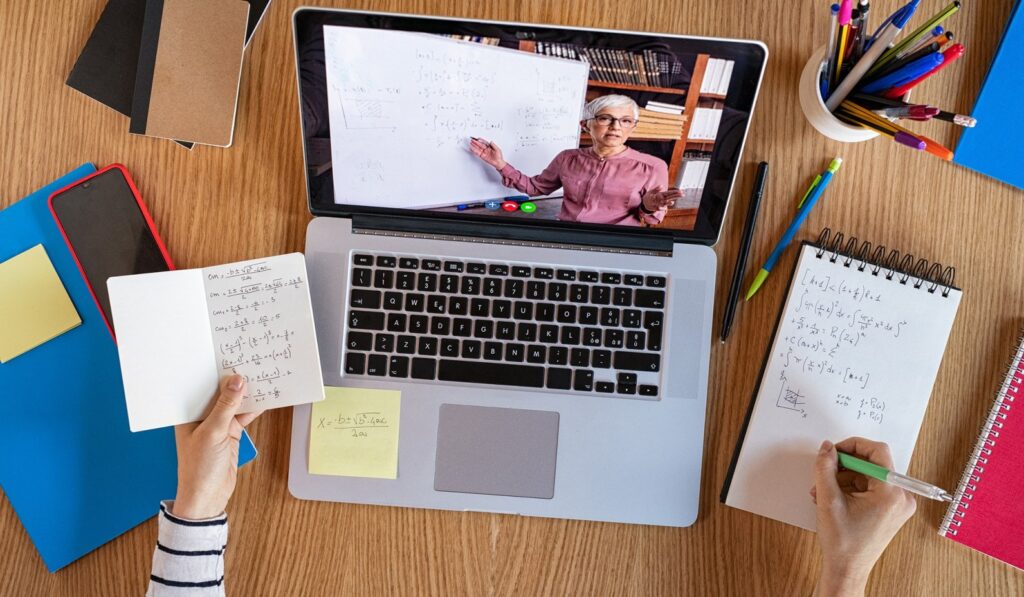

Just as online teaching and learning became a necessity for K-12 and postsecondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic, so too did online professional learning activities for educators at all levels. Not only have professional development (PD) activities primarily been held in virtual spaces over the last two years (both synchronously and asynchronously), but often the learning goals themselves have orbited around the use of educational technology in service of the immediate improvement of online teaching and learning experiences.

Of course, even prior to COVID-19, many professional learning and development enterprises took place online in order to meet the needs of busy educators. Asynchronous, “on demand” courses and workshops are commonly used for PD so that instructors may access materials whenever, and however frequently, they want. Additionally, online PD allows instructors to access valuable resources they might not otherwise have access to, both locally and globally. In a case study performed by Gaumer Erickson, Noonan, and McCall (2012), special education teachers in a rural district were able to collaborate with educators and experts in a non-rural district via an online PD enterprise. Participating teachers felt that the modality was an asset to their learning since they were given resources and feedback from experts the district might not otherwise be able to provide due to geography or lack of funding (Elliott, 2017).

As mentioned by participants in this case study, one of the key contributors to a successful professional learning experience is the opportunity to receive meaningful feedback. Feedback and participant interaction is part of an active professional learning experience wherein an adult learner is implementing their learning in an authentic, problem-based activity (Teräs & Kartoğlu, 2017). Feedback may come from a coach or instructor or from peers (or both), but regardless of the source, getting professional feedback is necessary in order to support learning implementation and critical reflection. Feedback can feel like an automatic and organic part of the learning process in face-to-face settings. For example, if an educator is being observed by a coach or mentor in their classroom, they would expect feedback to be shared directly following the observation. Similarly, if a peer group is working on a project together in a shared space or workshop, they will naturally give instant formative feedback, usually verbally, to each other as they collaborate.

What about with online PD? For context, the operational definition I’m using for online PD is any Internet-based form of learning or professional growth that an educator is engaged in (Elliott, 2017). How might feedback for professional development look similar or different in an online learning context? To what extent might feedback look different in an asynchronous environment? If PD is going to increasingly be situated in online environments, what tools are available to help assist in delivering meaningful feedback?

Teräs & Kartoğlu (2017) approach online professional development (OPD) through a framework called authentic e-learning. Authentic e-learning has a nine-point framework, the points of which are well supported in PD research and adult learning theories independent of the mode or learning environment (Teräs & Kartoğlu, 2017). The nine points for an authentic e-learning framework they propose are as follows:

1) Authentic context

2) Authentic tasks

3) Access to expert performances and the modeling of processes

4) Promoting multiple roles and perspectives

5) Collaborative construction of knowledge

6) Reflection

7) Articulation of understanding

8) Coaching & scaffolded support at critical times

9) Authentic assessment

Numbers 5, 8, & 9 are bolded on this list because each of these points requires interactions and communication among learners and instructors which will often take the form of meaningful feedback through a virtual medium. Within this learner-centered framework, technology should not be thought of primarily as a mode of delivering content. Rather, it should be viewed as a platform for facilitating interactions. Knowledge may be transferred using technology, but that’s not it’s most important role in e-learning. When technology is a conduit for a dynamic web of collaborative interactions, authentic e-learning can take place (Teräs & Kartoğlu, 2017). It’s certainly possible for information to be delivered in an asynchronous format using technology as the medium, but this shouldn’t be conflated with an authentic e-learning experience. Interaction are key.

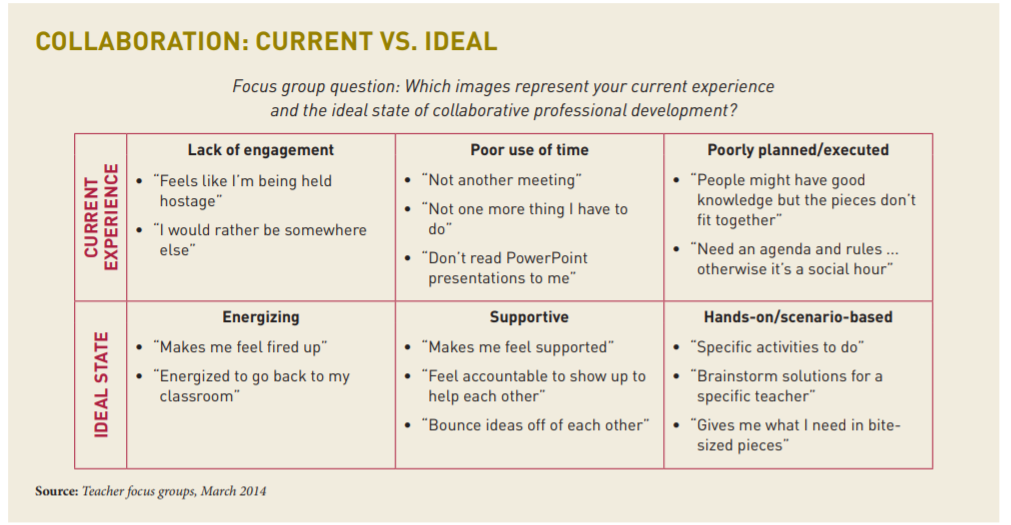

Perhaps one of the most effective ways to facilitate online interactions for professional development purposes is to create a Community of Practice (COP). Names for similar groupings that surface in the literature include Professional Learning Community (PLC) or a Community of Inquiry (COI). Despite any nuanced differences that may exist between the three, COPs, PLCs, and COIs have quite a bit in common. They are all entities distinct from formal learning and organizational structures, and are particularly valuable for their ability to extend beyond them. Members gather around shared experiences and/or goals and create their own communication channels and behavioral norms (Liu et al., 2009). These communities can exist within an organization, or they might consist of professionals across multiple organizations, but they are meant to facilitate the sharing of knowledge and tools and encourage critical discourse in a manner that is beneficial for professional growth for each of its members. COPs are inherently collaborative, and can often be formed around solving authentic, work-based problems (Liu et al., 2009). Though coaches, mentors, or experts may participate in COPs, peer interaction and collaboration are at the heart of a COP, and thus feedback is most often sourced from peers. COPs serve as a promising way to deliver timely, effective, relevant, and individualized support for adult learners while simultaneously decreasing the need for feedback coming solely from “experts.”

Online learning communities can be formed in a variety of different platforms, but regardless of the tech tool or medium, or whether the communities engage synchronously or asynchronously, COPs should have a medium in which they can engage in discussion, peer review, and collaborative problem-solving so that meaningful feedback may take place. Referencing a prior post in March of 2021 (Global research collaboration and the pandemic: How COVID-19 has accelerated networked learning in higher education), some notable computer-based platforms for collaborative enterprises include:

- Zoom (2011)

- Trello (2011)

- Basecamp (originally launched 2004, significantly updated 2012)

- Asana (2012)

- G Suite (2016)

- Figma (2016)

- Dropbox Paper (2017)

- Whimsical (2017)

- Microsoft Teams (2017)

This list represents nine, powerhouse collaboration platforms, all of which rolled out between 2010 and 2020, and many of which depend heavily on the power and popularity of cloud storage or cloud computing, such that platform users may interact and build upon one another’s contributions in both synchronous and asynchronous ways.

When attempting to collaborate asynchronously, especially where coaching or mentoring is concerned, video review software can be another important tool to consider. Teacher education programs or instructor professional development initiatives often use video review software to conduct remote classroom observations (though of course, video review may be used in a variety of fields for a variety of purposes). GoReact is just one example of video review software. This user-friendly review software offers users the opportunity to:

- Record and share videos easily using any kind of device, including smart phones

- Utilize cloud-based video storage so that recording, viewing, and grading can happen asynchronously

- Integrate video evidence seamlessly within common Learning Management Systems

- Give and receive time-stamped feedback on submitted video evidence, both written and recorded

Though I could likely spend a great many more hours discussing possible platforms to use in service of online learning communities, I wish to conclude with this simple, summative takeaway: quality PD requires feedback; therefore, effective PD conducted online must have ample space for interactions to take place among participants. It really is that simple.

References:

Elliott, J. C. (2017). The evolution from traditional to online professional development: A review. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 33(3), 114-125. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21532974.2017.1305304

Gaumer Erickson, A. S., Noonan, P. M., & McCall, Z. (2012). Effectiveness of online professional development for rural special educators. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31(1), 22–31.

Liu, W., Carr, R. L., & Strobel, J. (2009). Extending teacher professional development through an online learning community: A case study. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange (JETDE), 2(1), https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=jetde

SpeakWorks, Inc. (2021). GoReact. GoReact. https://get.goreact.com/

Teräs, H., & Kartoğlu, Ü. (2017). A grounded theory of professional learning in an authentic online professional development program. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7).