As has been noted by many educators at this point in the pandemic, it seems likely that the massive shifts to online teaching/learning that have taken place in the last year have permanently altered attitudes towards, and usage of, educational technology. Though most teachers, students, and families will be eager to return to the physical classroom as soon as it’s safe to do so, there’s no doubt that a hybrid approach to teaching and learning, both in K-12 and in higher education, is here to stay. This is true because of pragmatic constraints (i.e. some students and families will elect to continue with online learning into the Fall, even if in-person options are available), but also because of a more pervasive level adaptation such that hybrid teaching & learning has asserted itself as part of the “new normal” and will, in my opinion, be utilized well after the effects of the pandemic would mandate the use of technology-mediated modalities.

Hybrid learning (alternatively referred to as blended learning) at its most basic is an approach to teaching and learning that combines, or blends, face-to-face instruction with technology-mediated instruction (Saichaie, 2020). The actual ratio of face-to-face to online instruction can differ greatly and still be considered hybrid instruction; thus, a K-12 classroom may still be meeting in-person during traditional school hours and be participating in hybrid learning. Hybrid learning is also closely associated with the “flipped classroom” model of learning in which students are exposed to course content prior to class so that time in class allows students to “engage in higher-order thinking and application of the concepts in a group setting with the support of the instructor to foster deep and significant learning” (Saichaie, 2020, p.97). Effective hybrid teaching/learning will intentionally leverage the use of technology in order to replace seat time in a classroom and creatively engage students in learning in a variety of ways.

Konopelko (2020) offers some compelling suggestions as to why teachers and school districts might be more inclined to maintain hybrid or fully online learning modalities moving forward:

- Some students responded exceptionally well to the agency afforded by online, asynchronous learning. It’s possible that some sort of online learning option will need to remain accessible to students in public school systems in perpetuity.

- Advancements and investments in educational technology and, more specifically, interoperability have skyrocketed during the pandemic. Previously, it was common for teachers to be using many different curriculum softwares, interactive whiteboards, device-types, and student information systems that didn’t always communicate well with one another. Now, with tech giants like Microsoft investing major resources into expanding their virtual learning platforms, the integration of educational technology has become exceedingly easier and more effective in a short period of time (e.g. Microsoft Teams touting “Effective learning, all in one place”).

- Improvements to audiovisual tools/platforms have also been noticeable during the pandemic, opening the doors to broader use of video recordings and live, synchronous meeting sessions held virtually.

Additionally, I would suggest that:

- Many educators’ personal digital literacy and comfort with educational technology has exponentially increased during the pandemic as they’ve been forced to lean heavily (and creatively) on ed tech tools to continue teaching.

- The disruptive nature of the pandemic has created space for teachers to rethink how certain courses/subjects are taught with a mind towards student needs and student-centered learning. Hybrid teaching invites educators to “trim the fat” for lessons that have always been done a certain way, even as they recalibrate learning goals and think critically about student engagement. Student engagement can’t be taken for granted in a hybrid learning approach the way it might be in a physical classroom.

Thus, if we assume that hybrid teaching/learning using educational technology will, at some level, be a permanent fixture in education moving forward, it is important to pause and seriously consider the impact and potential of technology-mediated instructional practices. ISTE Standard 3 for educators asks instructors to consider how they can inspire students to positively contribute to, and responsibly participate in, the digital world. This standard is often closely tied to the concept of digital citizenship in that an instructor’s goal is to help learners act in socially responsible ways in digital spaces, exhibit empathetic behaviors online, think critically about online resources and their ethical use, and ultimately, build relationships and community as citizens with a stake in the virtual world. These aspects of digital citizenship are some of the many 21st century skills that are essential for learners to acquire in 2021.

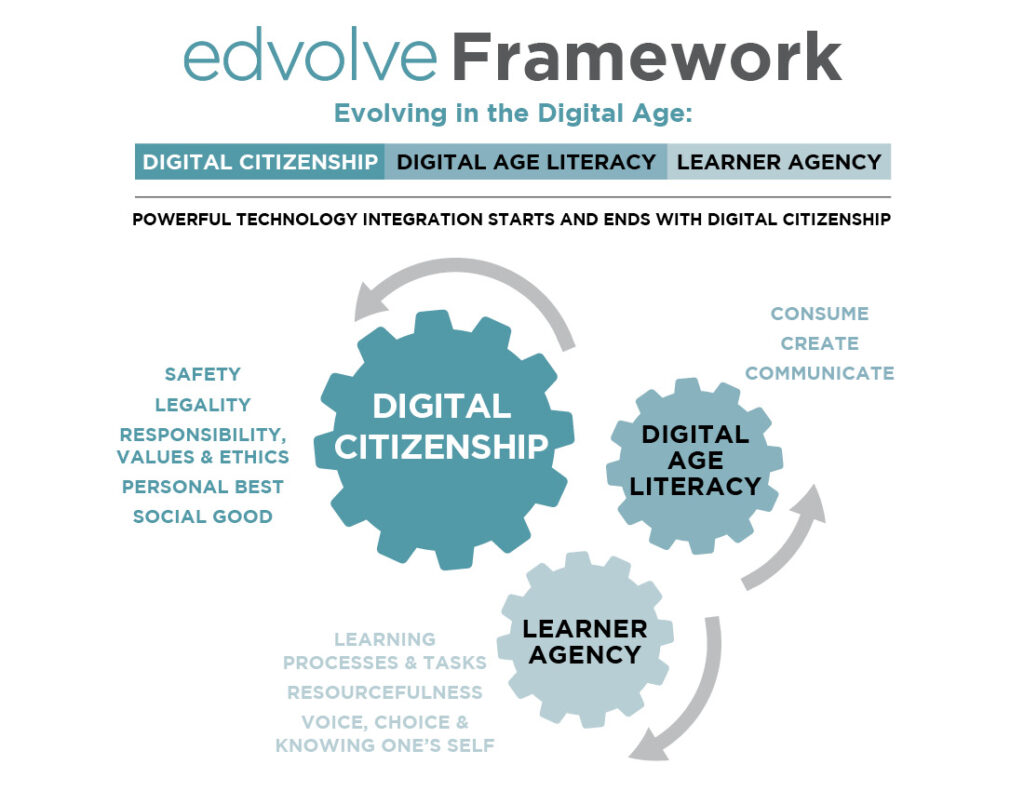

Of course, rather than adding another piece of content for instructors to cover in a classroom, digital citizenship development can/should be imbedded in instructional practice in an organic way. The Edvolve Framework put forth by Lindsey (2018) does a nice job of situating digital citizenship education within existing educational structures, noting that digital citizenship education isn’t about delivering more content, it’s about putting core values into practice within naturally occurring educational activities and technology use. In the Edvolve Framework, learner agency (attitude towards learning and personal responsibility) and digital literacy (consuming, communicating and creating with digital tools) work together to build a digital citizen (socially responsible participant in online environments), even as practicing digital citizenship will, in turn, improve learner agency and digital literacy skills (Lindsey, 2018). Like cogs in a machine, these three elements inform one another and mutually influence one another in all learning activities. Thus, with the Edvolve Framework as an example, it’s reasonable to assert that a hybrid learning model and the effective use of education technology can/should naturally lead to the cultivation of digital citizens.

Pedersen et al. (2018) refer to hybrid teaching as an entry point for practicing and expressing digital citizenship. More than any specific content, curriculum, or list of “dos and don’ts,” Pedersen et al. (2018) argue that digital citizenship is about becoming, belonging, and cultivating the capabilities to do so. Similarly, Emejulu and Mcgregor (2020) assert that

“…the cornerstone of a radical digital citizenship is the insistence that citizenship is a process of becoming – that it is an active and reflective state for individual and collective thinking and practice for collective action for the common good” (p.140).

There is something unique to hybridity that develops student thinking towards digital citizenship. “Thinking and acting in hybrid ways change the scope and space for education, making it more inclusive and conducive to the fostering of a digital citizenship that opens up to something other” (Pedersen et al., 2018, p. 234). Hybridity within education is the acknowledgement, and indeed the value of, otherness and difference, and it develops a learners’ ability to exist in in-between spaces in a globalized world (Pedersen et al., 2018). Hybridity, by definition, is the combination of more than one thing, and thus hybrid teaching and learning will not ascribe to one set of rules; rather, it will ask students to be flexible and practice resilience, thinking critically about the nuance of context and the shifting roles and expectations for themselves and others therein. Pedersen et al. (2018) argue that digital citizenship provides the “why” behind a hybrid educational enterprise, and that a value-based approach to teaching will inherently impact instructional design and, therefore, the learning experiences and goals. Hybrid teaching/learning with a digital citizenship “why” driving it will embody the following core values:

Shared value foundation for Hybrid Education (Pedersen et. al., 2018)

| Core Value | Underlying Value |

| Empathy | Care, Respect, Commitment, Compassion, Sensitivity, Invitational |

| Belonging & Building | Contribution, Sensitivity, Care, Generosity |

| Playfulness | Joy, Creativity, Curiosity, Exploration, Experimentation |

| Agency & Empowerment | Autonomy, Resourcefulness, Self-determination, Freedom, Autonomy, Courage |

| *Bildung | Thoughtfulness, Discipline, Professionalism |

| Discovery | Experimentation, Curiosity, Exploration |

Once again, these core values are not meant to be additive curricular elements; rather these values and the practice of digital citizenship should be organically imbedded in the learning process whenever educational technology or a hybrid approach to education is involved, and it is the essence of hybrid teaching/learning which will create space for these values to be cultivated in students.

It is also important to mention that hybridity, in contrast to a learning environment that is fully online, has unique benefits in that students are, to some extent, still situated in a physical environment, and therefore the cultural, and sociopolitical realities (and limitations) that are part of that physical environment. Emejulu & McGregor (2019) assert that a digital citizenship that is seemingly neutral, nomadic, agnostically tolerant, and primarily concerned with effective network extension and demonstrating ‘netiquette’ in virtual spaces is, at best, incomplete. They argue that digital citizenship must be situated within social, economic, and political contexts in order to be meaningfully practiced. Indeed, a ‘radical digital citizenship’ asks citizens to think about the consequences of digital technologies in everyday life and consider “who has the power” wherever technology is used (Emejulu & McGregor, 2019). The authors assert that digital citizenship can’t just be about improving virtual spaces; rather, active digital citizenship should be situated in the ‘real world’ and help us engage with “social, economic, and environmental inequalities in a new and different way” (Emejulu & McGregor, 2019, p. 143).

In summary, the specific tools and learning platforms used to engage in hybrid teaching/learning are less important than the overall vision for what hybridity, as an ethos, can accomplish. A hybrid teaching/learning model is uniquely valuable in its ability to organically cultivate digital citizens, and will go a long way to helping students become resilient, socially responsible, empathetic, competent, and creative participants in both virtual and physical spaces. After all, education makes both the “becoming of the individual and the renewal of the common world possible,” and digital education is no exception (Pedersen et al., 2018, p. 227).

References

Emejulu, A. & McGregor, C. (2019). Towards a radical digital citizenship in digital education. Critical Studies in Education (60)1, 131–147 https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1234494

Konopelko, D. (2020, May 7). Post-Pandemic classrooms: What will they look like and how will they be different? EdTech. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2021/05/post-pandemic-classrooms-what-will-they-look-and-how-will-they-be-different

Lindsey, L. (2018). Edvolve Framework, Evolving in the Digital Age: Digital Citizenship, Digital Age Literacy, Learner Agency. Edvolve Learning. https://www.edvolvelearning.com/framework.html

Pedersen, A.Y., Nørgaard, R.T., & Köppe, C. (2018). Patterns of inclusion: Fostering digital citizenship through hybrid education. Educational Technology & Society 21(1), pp. 225-236. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26273882?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Saichaie, K. (2020). Blended, flipped, and hybrid learning: Definitions, developments, and directions. New Directions for Teaching & Learning 164, 95-104. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20428