Like so many other countries across the globe, higher education institutions in South Africa were forced to reckon with a rapid pivot to online teaching/learning in order to maintain operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the 26 public universities in South Africa, 25 are residential institutions that did not allow distance education prior to 2014 (Czerniewicz et al., 2020). This scramble to change modalities in 2020 came on the coattails of nationwide student protests from 2015-2017 during which typical campus activities and courses were repeatedly interrupted at some of the largest public institutions because of the #FeesMustFall movement, a student-led initiative boycotting swift, large, and prohibitive hikes in tuition costs instituted by the South African government. At the heart of the #FeesMustFall movement was attention to the fact that systemic racism and resource inequalities left historically marginalized students most unable to cope with the tuition increase. Unsurprisingly, the scope and scale of online teaching/learning suddenly required during the Pandemic only further accentuated the obvious issues of access and equity as reflected by university students in South Africa, particularly in regards to the digital divide among the South African student population. When students had access to usual campus infrastructures, they were able to utilize tools like free Wi-Fi, libraries, and computer labs which reduced some level of disparity in regards to technology access (Swartz et al., 2018). When this access was taken away, many existing inequalities were made starkly visible, and students without expansive resource networks were left adrift.

“Across the nation, the pandemic revealed historic (and mostly forgotten) fault lines, and as silence settled down upon buzzing cities and communities and we all came to a standstill, we were forced to hear the tectonic layers pushing and shoving against one another, tectonic layers of intergenerational inequalities, unheard and ignored for too long.”

Czerniewicz et al., 2020, para. 14

This quote might just as easily be referring to the United States, especially in the weeks and months following the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020 and the ongoing discourse about racial tensions and inequalities embedded in American systems. Indeed, the relative ‘silence’ ushered in by the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the consistent hum of existing inequalities imbedded within communities, throughout countries, and across international borders which significantly impacted the ability for students at all levels to continue in their learning (or not).

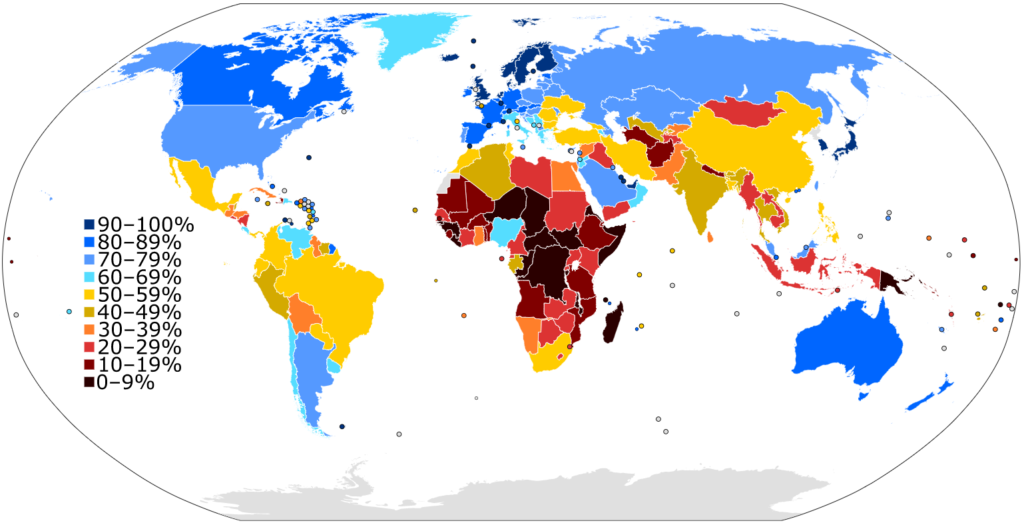

Source: International Telecommunications Union.

In light of the socio-political factors influencing teaching/learning in COVID-19, Czerniewicz et al. (2020) set out to analyze how issues of equity and inequality played out in the pivot to online teaching/learning in South African higher education during the pandemic, and how these concerns might have implications or offer guidance for the educational enterprise post-pandemic. In this case study, nine themes on access & equity emerged which, almost certainly, will find echoes among educators and school administrators worldwide. Some themes serve as cautions and highlight system failures, while some highlight the possibilities and opportunities afforded through online teaching/learning:

- Inequalities Made Visible: the crisis made preexisting inequalities and infrastructure failures starkly visible; this included poorly-constructed pedagogies that previously failed to meet the varied and nuanced needs of real university students (as opposed to the disembodied ‘ideal’ student), crisis notwithstanding.

- Imbedded in Context: the sudden shift to online teaching/learning took place within embedded contexts where gender, culture, race, geopolitical context, etc., played a part in a student’s lived experience; all influencing factors must be considered intersectionally in the learning environment, online or otherwise.

- Multimodal Strategies: it became clear that in order to even come close to meeting student needs for remote learning, a ‘multimodal’ or ‘hyflex’ approach was required; this meant course content had to be highly accessible through multiple media formats, some of which were not digital.

- Making a Plan: pre-existing emergency plans for instruction at both the institutional and instructional level are a necessity and must include provisions for unreliable electrical power or internet access.

- Digital Literacy: student levels of digital literacy and capacity for effective navigation of e-learning tools cannot be assumed; neither can assumptions be made of the faculty/staff responsible for implementing digital learning tools.

- Places of Learning: in lockdown, many students, faculty, & staff, no longer had a dedicated space to be able to engage in their scholastic duties. Students/faculty/staff were unevenly impacted and had to make substantially different sacrifices depending on their circumstances (e.g. parents with young children at home, students caring for elderly relatives, etc.)

- Parity of Pedagogy: the crisis forced learning design to become more student-centered than ever before. Though there were certainly gaps and failings, instructors were re-thinking assessment strategies and intervention options in comprehensive ways.

- Sectoral Stratification: similar to the first theme, the pandemic highlighted existing inequalities, this time at the institutional level. Larger/smaller, urban/rural, ranked/not ranked universities all faced different kinds of obstacles. Historically advantaged institutions fared better in their emergency responses.

- Social Responsibility in Higher Education: The boundaries between higher education and larger society are porous. Universities cannot pretend they are neutral when it comes to social and economic inequities.

Perhaps central to each of these themes is a need for student-centered learning design and careful consideration for the extent to which stakeholders have access to internet and a suitable device. The pandemic has shown the urgent need to teach and support student learning no matter where they live or what resources they personally possess (Correia, 2020). In support of the third theme listed above (multimodal pedagogical strategies), Correia (2020) offers an array of concrete tools and strategies for low-bandwidth online teaching/learning that can help mitigate the impacts of the digital divide in digital education environments:

- Start designing a course with three assumptions in mind: 1) The student may have limited bandwidth, data, or internet access with which to participate in the course 2) The student may be much less familiar with the technology being used than the instructor, and 3) They may not have access to tech equipment like cameras, printers, and scanners

- Make frequent contact and learn about student accessibility needs. Consider the use of postal mail (with postage cost covered), landline phone calls, chat check-ins, and asynchronous video messages.

- Consider how to incorporate a students’ informal learning and life experiences into course assignments and objectives; in other words, lean in to student learning that occurs offline.

- Use free resources and tools profusely. OER Commons is just one example of a public digital library of open educational resources. Bear in mind, however, that where assignments are concerned, internet access may bar frequent usage, even if the tool is free.

- Utilize pre-recorded lectures and transcripts for students unable to join synchronous video conferences

- Use audio recordings as educational resources (e.g. podcasts), as well as for instructor-student communication. Audio recordings often result in fewer tech issues and use less bandwidth; they mitigate the need for a camera along with possible feelings of intrusion or shyness that cameras can bring.

- Use alternative forms of assessment which may include portfolios, open book examinations, or discussion forums.

Of course, COVID-19 did not usher in the dawn of online education. The demand for digital education in its various forms has been growing steadily over the course of the last decade, even prior to the pandemic (Xie et al., 2020). It’s increase in popularity can largely be credited to the possibilities it provides for access and equity, including opportunities for flexibility, efficiency, the promotion of innovative and student-centered teaching strategies, access to varied (and often free) sources of information, access to global research and collaboration, and increased access/reduced costs for higher education, especially for students who couldn’t otherwise afford to attend a residential university (Xie et al., 2020). The comprehensive demands for remote teaching/learning during the pandemic has merely accelerated the adoption and acceptance of online teaching/learning in all kinds of educational settings, and it’s fair to assume that a certain level of online teaching/learning integration will define the “new normal” in education moving forward (Xie et al., 2020). Educators and educational institutions, then, must be able to recognize the potential pitfalls for access and equity as it pertains to digital education. To the extent that online teaching/learning is here to stay, educators can’t afford to ignore student needs and the ways online teaching/learning might be insufficient to meet them. And yet, there remains significant potential.

“[The pandemic] has brought into focus numerous examples of extraordinary resilience, networks and…unexpected alliances of collaboration and support, including inspiring creativity, examples of technology used for equity purposes and moments of optimism. …There is an opportunity in the moment for genuine equity-focused innovation, policymaking, provision and pedagogy.”

Czerniewicz et al., 2020

References

Correia, A. (2020). Healing the digital divide during the COVID-19 pandemic. Quarterly Review of Distance Education 21(1), 13-21. https://ezproxy.spu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=a9h&AN=146721348&site=ehost-live

Czerniewicz, L., Agherdien, N., Badenhorst, J., Belluigi, D., Chambers, T., Chili, M., de Villiers, M., Felix, W., Gachago, D., Gokhale, C., Ivala, E., Kramm, N., Madiba, M., Mistri, G., Mgqwashu, E., Pallitt, N., Prinsloo, P., Solomon, L., … Wissing, G. (2020). A wake-up call: Equity, inequality and Covid-19 emergency remote teaching and learning. Postdigital Science and Education 2, 946–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00187-4

Swartz, B.C., Gachago, D. & Belford, C. (2018). To care or not to care – reflections on the ethics of blended learning in times of disruption. South African Journal of Higher Education 32(6), 49‒64.

Xie, X., Siau, K., & Nah, F. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic – online education in the new normal and the next normal. Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research 22(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/15228053.2020.1824884