According to the National Science Foundation (2019), one out of every five academic research articles are written by authors hailing from more than one country. This fact suggests that the value of international research collaboration was recognized and sought out well in advance of the global COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, but perhaps it’s only just the beginning. Reasons to pursue global collaboration in higher education include reaching wider audiences and increasing the impact of published research, reducing bias and broadening perspectives with a diverse research team, and leveraging the ability to offset domestic skill shortages by collaborating across national borders (Lee & Haupt, 2020). Networked learning in higher education can also encourage new levels of creativity and innovation in all kinds of disciplines, and it expands the potential for authentic global and cultural learning experiences in an increasingly connected world (Cronina et al., 2016). These benefits apply to even the most scholastically “productive” countries like the USA and China (Lee & Haupt, 2020). That said, understanding that international collaboration in higher education was valued–at least to a certain extent–prior to 2020, I am curious to explore how recent changes in technology and cultural shifts in academia during the pandemic have worked in tandem to build upon this trend, potentially accelerating technology’s impact on global research collaboration and cooperation into the future.

With the onset of COVID-19, scientists and researchers from every corner of the world scrambled to understand the virus and seek a cure. Information sharing among countries quickly became essential, especially for those countries that were hardest hit early on (Lee & Haupt, 2020). Though socio-political tensions between countries–and even domestically within countries–were hardly in short supply in 2020, the demands of the pandemic shifted priorities such that many international corporations and research institutions began working together rather than competing with each other to produce a vaccine, and large-scale exchanges of medical and public health data, including possible solutions, was (and still is) shared internationally using digital and online tools (Buitendijk, 2020).

When it comes to information sharing, one way of measuring an increase in international collaboration is through a country’s participation in open access publication platforms. Open access journals and publication platforms remove barriers for accessing information and research since they do not require payment or subscriptions in order to be read and cited. Sometimes the cost of publishing is absorbed by these open access platforms through philanthropic efforts, sponsorship, or submission fees paid by the authors, etc., but the bottom line is that there’s typically little profit to be made by academics, researchers, and authors who publish in open access platforms. Thus, the motivation for researchers–either individually or nationally speaking–to publish in an open access platform is often more altruistic in nature, placing higher priority on the sharing of information than any potential gains or notoriety received from publishing, monetary or otherwise. According to Lee & Haupt (2020), countries with lower GDP who were more severely affected by the pandemic were the most likely to increase participation in open access publishing and international research efforts. It would follow that decisions to increase open-access participation was also meant to illicit reciprocal behavior from other countries, and indeed, the majority of all “knowledge producing” countries increased their participation in open access publishing during the pandemic: “For each of the top 25 COVID-19 research-producing countries, there was a noticeably higher proportion of open-access articles on COVID-19 than during the past 5 years and on non-COVID-19…publications during the same period” (Lee & Haupt, 2020, para. 26).

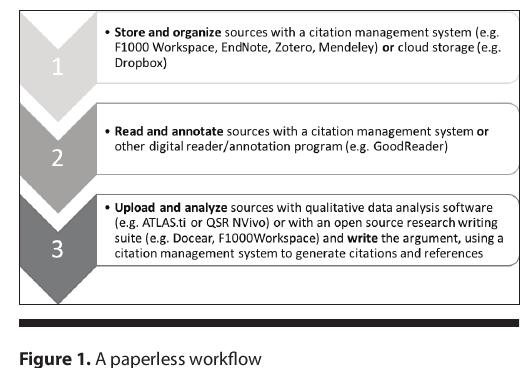

In addition to the public health concerns that have motivated scholars and researchers to participate in more information sharing during the pandemic, it must also be said that the act of collaboration has gotten exponentially easier in recent years. In a 2010 publication, Iorio et al. discuss the use of digital tools designed to facilitate international collaboration and interaction amongst higher education scholars. In this specific case, domestic teams in five different areas of the world were attempting to complete an integrative design task which required synchronous virtual meetings, a way to exchange ideas, brainstorm, and problem solve in real time (though not necessarily synchronously), as well as an appropriate digital repository for their work (building plans, model mapping, cost estimates, etc.) which could be accessed frequently by the members of each team in their respective countries. The article focused its efforts on reviewing the virtual reality platform Second Life. To me, Second Life now feels woefully insufficient as a project management platform, at least according to 2021 standards, but at the time, the authors found Second Life to be a comparatively “appealing choice” due to its options for customization and tools such as virtual white boards, voice and text chat, scheduling agents, etc., all in one centralized, virtual location. Second Life aside, the authors noted that “To date, very few technological options exist that provide all of [the needed] functionalities to distributed networks. Commonly used tools such as email, instant messaging, and teleconferencing do not provide a framework for interaction that fully satisfies the demands of geographically distributed projects.”

In short, Second Life was more or less the best this research team could find in 2010. Since then, there’s been a massive influx of virtual project management/collaboration platforms introduced to the market. Consider the list below of some of the “big names” in collaboration software along with their launch dates:

- Zoom (2011)

- Trello (2011)

- Basecamp (originally launched 2004, significantly updated 2012)

- Asana (2012)

- G Suite (2016)

- Figma (2016)

- Dropbox Paper (2017)

- Whimsical (2017)

- Microsoft Teams (2017)

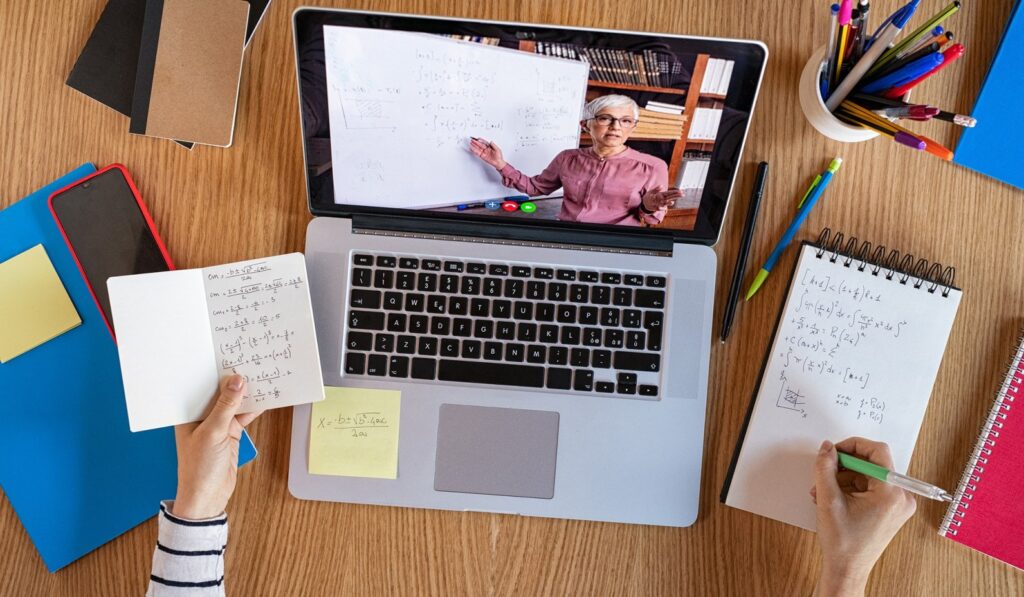

This list represents nine, powerhouse collaboration platforms, all of which rolled out between 2010 and 2020, and many of which depend heavily on the power and popularity of cloud storage or cloud computing (which was also expanding significantly during this time frame). And please note: this list is hardly exhaustive. There are many more out there (and counting!), and even the ones on this list are constantly being updated and expanded. Each platform or collection of tools on this list boasts its own strengths and weaknesses (the exploration of which is not the point of this post), but there can be no doubt that no matter the platform, it is easier to make the choice to communicate, collaborate, and innovate with people all over the world in 2021 than it was even ten years ago. Of course, not only have the tools themselves gotten better, but the pandemic has accelerated digital tool adoption for purposes of collaboration at an extraordinary rate, popularizing already existing tools (e.g.. Zoom teleconferencing) in unprecedented ways, such that millions, if not billions, of students and professionals in myriads of settings worldwide are collaborating and problem solving virtually across distances in ways they were not one year ago.

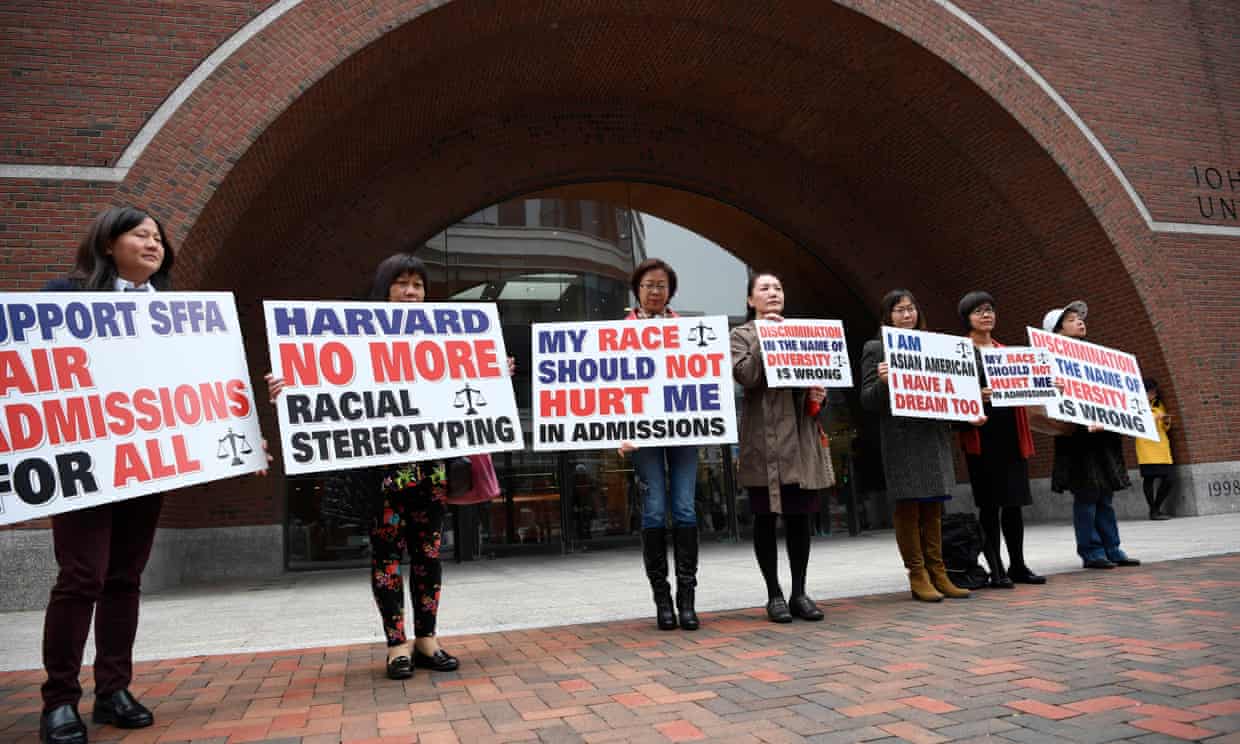

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into stark realization the fact that we need ‘global solutions to global challenges’ (Buitendijk et al, 2020) and that we need not relegate the phenomena of increased global collaboration in higher education to a particular moment in time. Instead, we might view this as an opportunity to challenge the model of competition between higher education institutions and place lasting value on diversified bodies of knowledge production, dissemination, and consumption (Buitendijk et al, 2020). We might also recognize that a philosophy of collaboration makes it possible for students and lecturers in all types of higher education settings to have more equal roles in creating content, sharing resources, and asking/answering important questions (Cronina et al., 2016). As centers of research all over the world, universities have a crucial role to play in helping humans to better care for one another on a global scale, teaching us to become “more empathic, less competitive, and more networked in our research and educational activities” (Buitendijk, 2020). Let us not lose the momentum of this moment to embrace a new norm in higher education, maintaining a sincere commitment to, and value of, community-minded research and collaboration across borders.

References:

Buitendijk, B., Ward, H., Shimshon, G., Sam, A., & Sharma, D. (2020). COVID-19: An opportunity to rethink global cooperation in higher education and research. BMJ Global Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002790

Cronina, C., Cochraneb, T., & Gordonc, A. (2016). Nurturing global collaboration and networked learning in higher education. Research in Learning Technology, 24.

Iorio, J., Peschiera, G., Taylor, L., & Korpela, L. (2010). Factors impacting usage patterns of collaborative tools designed to support global virtual design project networks. Journal of Information Technology Design in Construction, 16, 209-230. https://itcon.org/papers/2011_14.content.08738.pdf

Lee, J., & Haupt, J. (2020). Scientific globalism during a global crisis: research collaboration and open access publications on COVID-19. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00589-0

National Science Foundation (2019). Publications Output: U.S. Trends and International Comparisons. National Science Board: Science and Engineering Indicators. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20206/executive-summary