As a former classroom teacher, I am deeply aware of the potential professional development (PD) activities have to positively improve teaching practice; it’s the same potential that PD has to overwhelm instructors and use up valuable time, energy, and resources that might have been used elsewhere in jam-packed school schedules.

When it comes to effective use of educational technology and online teaching in particular, thoughtful, engaging, and practical PD is essential. Of course, with the onset of COVID-19, schools and instructors at every level were required to make rapid, comprehensive pivots to online teaching and learning, and ed tech specialists, coaches, and instructional designers found their hands full with the overwhelming need for support and training teachers needed in a condensed time frame. There’s no doubt that the emergency shift to online teaching and learning necessitated by the pandemic was immensely challenging for both students and educators, but it’s also fair to say that there has been more than a few success stories related to online teaching and learning, some of them because of effective PD efforts that were made well in advance of the pandemic. Considering this, I am curious to explore some recent exemplars of professional development activities in higher education related to pivots to online teaching/learning, COVID-related or otherwise.

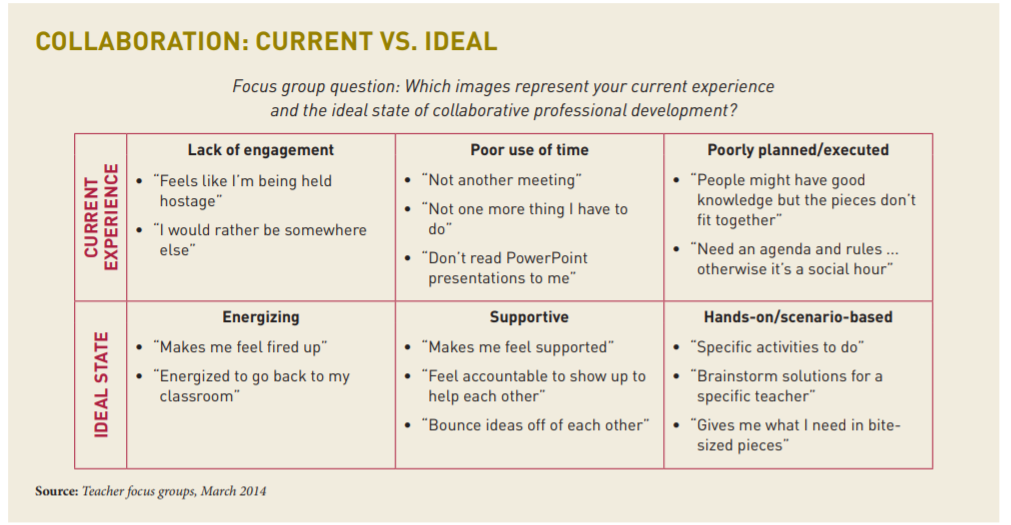

To frame this exploration, it’s helpful to first examine some of the research shaping current approaches to PD in education. In 2014, the Boston Consulting Group working on behalf of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation surveyed over 1,300 stakeholders in education (teachers, administrators, instructional coaches, etc.) on topics related to PD (BCG, 2014). Research suggested that teachers at all levels were overwhelmingly dissatisfied with the majority of PD offerings. Reasons cited included a disconnect between classroom observations by administrators and meaningful coaching interactions, a lack of trust or authority from those leading the PD initiatives, PD presented as an exercise in compliance instead of a meaningful opportunity for growth, lack of opportunity for collaboration with peers, lack of choice, and lack of relevance to immediate needs (BCG, 2014). Suggestions for future practice included a decreased dependence on external vendors for PD workshops and increased attention to teacher-driven needs and collaboration time, as well as considerations for leveraging technology to boost collaboration and streamline workloads (BCG, 2014).

These findings were also supported by Cho & Rathburn’s 2013 case study on PD in higher education. Similar to the findings of the Boston Consulting Group, Cho & Rathburn (2013) found that a traditional workshop format for higher education PD constrained active participation, collaboration, and the creation of usable knowledge for teaching. Cho & Rathburn (2013) proposed a problem-based learning framework for PD in higher education which:

- Lets relevant problems guide the learning activities

- Has participants self-direct their learning and take responsibility for knowledge acquisition

- Encourages social interaction and collaborative knowledge construction among instructors.

Data from this particular case study supported a teacher-centered approach to PD. It was favored by university instructors and facilitated the creation of usable knowledge which could be immediately applicable in their own teaching contexts. In this case study, the PD opportunities were provided online and asynchronously in order to counteract constraints of time and place and allow instructors to engage with the PD as it was fitting for their individual departments (Cho & Rathburn, 2013).

In another look at PD initiatives in higher education, Schildkamp et al. (2020) make note of the presence of certain “building blocks” which made for effective professional development and use of educational technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this research, the two PD initiatives examined by Shildkamp et al. (2020) were effective because they prioritized:

- The effective use of technology and ways it might need to be customizable to specific content area needs

- Active learning activities supported by experts

- Clearly defined goals focused on the instructor’s own practice and use of technology with attention to long-term sustainability

In an effort to highlight and streamline some of the similarities and standouts of the research initiatives mentioned above, I find it helpful to reference Vicki Davis’s list of tips for highly effective PD activities that can serve as a meaningful guide for PD facilitators and coaches in any academic environment (Davis, 2015):

1. Use What You Are Teaching: don’t just lecture about a helpful strategy or tool, model it and have participants actively engage with it

2. Develop Something That You’ll Use Right Away: if it’s relevant, instructors should be able to implement a takeaway within a few weeks

3. Receive Feedback: create opportunity for feedback on the PD “session” as well as peer-to-peer feedback on implementation of the takeaway

4. Improve and Level Up: create opportunities to workshop the initial takeaway with ongoing PD and support; effective PD isn’t “one and done”

5. Local Responsibility and Buy-In: institutional/school-wide support is needed, it’s not just the responsibility of teachers/instructors to internalize and implement PD initiatives

6. Long-Term Focus: avoid the temptation to chase fads or take a “flavor of the week” approach to PD (especially in regards to technology) which can make takeaways feel disconnected, erratic, and short-lived; make sure PD aligns meaningfully with long-term goals of the school/district/institution

7. Good Timing: consider the larger ebb and flow of the academic calendar and when instructors will be in the best position to be fully present for a PD initiative

8. Empower Peer Collaboration: give teachers/instructors the time and opportunity to learn from one another.

Finally, I’d like to highlight a comprehensive example of effective PD for online learning sourced from a community college in Hawaii. This approach to PD places professors in the seat of the student in an online learning context, and it puts many of the tips listed above into action. At Kapi’olani Community College on the island of Oahu, Instructional Designer Helen Torigoe was charged with training faculty in the process of converting courses for online delivery (this was prior to the onset of the pandemic). In response, Torigoe created the Teaching Online Prep Program (TOPP) (Schauffhauser, 2019). In TOPP, faculty participate in an online course model as a student, using their own first-hand experience in the program to inform their course creation. As they participate in the course, faculty are able to use the technology that they will be in charge of as an instructor (which include programs like Zoom, Padlet, Flipgrid, Adobe Spark, Loom, and Screencast-O-Matic), gaining comfort and ease with the tools and increasing their overall digital literacy. Faculty also get a comprehensive sense for the student experience while concurrently creating an actual course template that they will use in the near future. Instructors receive guidance, feedback, and support from the TOPP course coordinator and their peers in the course. Such training is mandatory for anybody teaching online for the first time at Kapi’olani Community College. A “Recharge” workshop has also been created to help faculty engage in continued learning for best practice in digital education. This ensures that faculty do not become static in their teaching methods as they are consistently exposed to new tools and strategies, while also gleaning reminders and refresh opportunities in support of long-term sustainability (Schauffhauser, 2019). Institutions that participate in online education need to provide adequate training in both pedagogical issues and technology-related skills for their faculty, not only when developing and teaching online courses for the first time, but as an ongoing priority in faculty professional development (Bolliger et al., 2014).

I am curious to know how Kapi’olani Community College fared during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic and how faculty and students dealt with the switch to fully remote learning, especially those who weren’t previously involved with distance learning initiatives. Was TOPP used to onboard instructors who previously only taught face to face? Did faculty feel like they had the resources and training they needed to make the switch more effectively than colleagues at other institutions? These aren’t questions I have answers to, but I venture to guess that faculty and instructional designers at Kapi’olani Community College did indeed have a leg up because of the prior investments the institution had already made in timely, meaningful, applicable, teacher-driven, problem-based, technology-rich, and sustainable PD.

References:

Bolliger, D. U., Inan, F. A., & Wasilik, O. (2014). Development and Validation of the Online Instructor Satisfaction Measure (OISM). Educational Technology Society, 17(2), 183–195.

Boston Consulting Group (2014). Teachers know best: Teachers’ Views on professional development. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://usprogram.gatesfoundation.org/news-and-insights/usp-resource-center/resources/teachers-know-best-teachers-views-on-professional-development

Cho, M. & Rathbun, G. (2013). Implementing teacher-centred online teacher professional development (oTPD) programme in higher education: a case study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(2), 144-156. 10.1080/14703297.2012.760868

Davis, V. (2015, April 15). 8 Top Tips for Highly Effective PD. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/top-tips-highly-effective-pd-vicki-davis

Schaffhauser, Dian. (2019, October 30). Improving online teaching through training and support. Campus Technology. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2019/10/30/improving-online-teaching-through-training-and-support.aspx

Schildkamp, K., Wopereis, I., Kat-De Jong, M., Peet, A. & Hoetjes, I. (2020). Building blocks of instructor professional development for innovative ICT use during a pandemic. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(3/4), pp. 281-293. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-06-2020-0034

I agree with the list you shared about effective PD strategies. As I think about the list, I keep coming back and mulling over #6 – how much needs to be strategic focused and how much needs to be responsive and kind of incorporate the flavor of the week. Under normal circumstances, I think there was more bandwidth to spend time on thinking how to strategically move towards an institution goal, but with the pandemic, I think it also showed a need to know what’s going on with instructors and adapt and provide just-in-time or flavor of the week style options. In some ways, I’m okay with the disconnect as long as the team offering the training can say why and identify their audience.

Another thing I’m wondering about is how to do both more consistently, maybe something like what FLO does on twitter, where each day has a theme, but shares current issues and content related to that theme. Where would you draw a line between a strategic focus vs what’s up this week type of PD?

I enjoyed your post Katie! You formatted this very well so the reading flowed naturally (I must show appreciation for this as an English teacher!). I especially liked the list for highly effective PD. Thanks!

After reading your post, I guess I try to Rediscover the advantages of PD. Most of the time, I personally don’t enjoy a One-way lecture-style training that PD does a lot of time. But if PD can be clearly set with a purpose, and focus that can be helpful. Your post is informative; I enjoy it a lot.